1. Introduction

When we visit a website, our browsers often receive small text files called cookies. These cookies hold information that the website or other authorized entities can read. At first glance, cookies seem like harmless tools that help websites remember our preferences or logins. However, cookies also serve a key role in tracking user behavior across the web. Whether reading news, shopping online, or browsing social media, cookies can keep tabs on our visits and actions. This leads to questions about how cookies contribute to data collection, their methods, and their implications for user privacy.

In this tutorial, we examine how cookies enable tracking and discuss the difference between first-party and third-party cookies. We’ll also look into the legal landscape governing their use and consider what the future holds as browsers and regulators respond to privacy demands.

2. Cookies Basics

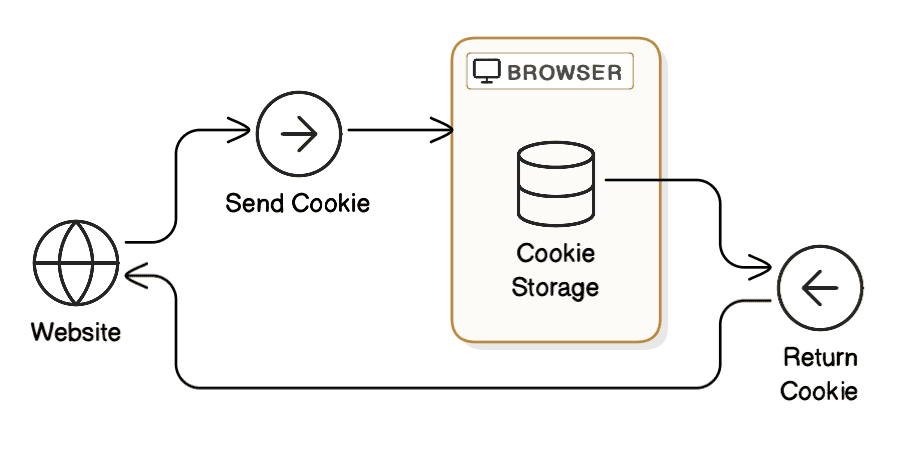

A cookie is a short text sent by a website to a browser. The browser stores this cookie and sends it back to the same site on subsequent visits:

Typically, cookies contain simple key-value data that might identify a session, remember the chosen language, or keep other basic details. For instance, when a user selects a preferred language on a website, the site can set a cookie holding that choice. On the next visit, the site reads the cookie to present the content in that language without asking again.

Initially, the web tracks users as they move from one page to another. Each request was separate, and the server had no direct memory of previous visitors. Cookies were introduced to solve this problem by allowing the server to recognize that the same browser had returned.

For example, a cookie can store a session identifier when a user logs into an account. The browser returns the cookie the next time the user clicks a link on the same site. The server checks the cookie’s session identifier and sees that this visitor is already logged in, so there is no need to ask for the password again. This practical and convenient solution improved user experience and made the web more interactive.

Over time, as online advertising and analytics became more important, cookies moved beyond just remembering session states. Because cookies can last longer than a single page view, they are useful for building a record of user activity. A cookie might store a user’s unique ID. If this ID is associated with many events, such as visits to various pages or clicks on certain links, it becomes possible to piece together a detailed profile. This profile can be even more comprehensive if multiple sites rely on the same advertising partner or analytics service that reads a shared cookie. This way, a cookie transforms from a simple convenience tool into a tracking method.

3. Examples of Cookies

Let’s say we have a simple website, and when the user selects a language, the server sets a cookie to store this choice. In HTTP, cookies are set using response headers. When the server responds, it can send a line such as this one:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Set-Cookie: preferredLanguage=en; Path=/; Max-Age=3600

In this response, Set-Cookie: preferredLanguage=en; Path=/; Max-Age=3600 tells the browser to store a cookie named preferredLanguage with the value en. The Path=/ means this cookie will be sent for all paths on the site. The Max-Age=3600 means it will last for one hour. On the user’s next visit to any page on this site, the browser includes the cookie in the request:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Cookie: preferredLanguage=en

The server reads this cookie and presents content in English without prompting the user again.

We can also set or read cookies using JavaScript in the browser on the client side, although modern privacy practices discourage widespread cookie manipulation on the client side. Suppose we have a simple script that sets a cookie to remember a user’s theme preference:

// Setting a cookie using JavaScript

document.cookie = "theme=dark; path=/; max-age=86400";

This code tells the browser to store a cookie named theme with the value dark, valid for one day (86,400 seconds). The browser will send this cookie to the server in every subsequent request.

We can also read the cookies that are stored in the browser:

// Reading all cookies in JavaScript

const allCookies = document.cookie;

console.log(allCookies);

This might produce a string like “referredLanguage=en; theme=dark“. We can split the string by ; and parse each key-value pair to handle the cookies individually. For example:

const cookies = document.cookie.split('; ').reduce((acc, cookieStr) => {

const [key, value] = cookieStr.split('=');

acc[key] = value;

return acc;

}, {});

console.log(cookies.theme); // "dark"

console.log(cookies.preferredLanguage); // "en"

In a simple scenario, these cookies just store a few user preferences.

4. How Cookies Enable Tracking

However, consider a more complex example, where a large advertising network places a cookie on multiple sites. Each site includes a small resource from the same advertising domain, like a tracking pixel. Each time the user visits a site with this pixel, the browser sends the advertising network’s cookie along with the request. As a result, the advertising network sees the same cookie ID appearing on different sites.

Over days or weeks, the network can create a detailed user profile about what the user likes, what news pages they read, what products they look at, and incorporate other behavioral signals.

Cookies themselves are not inherently malicious. They are just pieces of stored data. The tracking aspect comes from how websites and advertising networks use the stored information. A website can recognize that the same individual returns later by assigning a unique identifier to a user through a cookie. Over time, the site can build a profile: which pages does this user view, for how long, in what sequence, etc.?

The collected data can be combined if these cookies are tied to analytics systems or advertising platforms. For instance, if a user visits a shopping site and browses a set of products, a cookie may record their interests. Later, the user might see targeted ads on a different site provided by an ad network that has read the same cookie or a related identifier. This way, cookies link user actions and the databases that store those actions for future reference.

The tracking process is subtle and usually hidden from immediate view. Users might not realize how their browsing patterns form a continuous line of recorded activity. Without cookies, it would be challenging to pinpoint that the same browser visited page A on Monday, page B on Tuesday, and then clicked on a product ad on Wednesday. Cookies supply the persistent thread that connects all these separate events.

5. First-Party vs. Third-Party Cookies

Not all cookies serve the same role. There’s a crucial distinction between first-party and third-party cookies.

First-party cookies are placed by the website we are currently visiting. For example, if we visit an online bookstore, the cookie that keeps track of our cart items or login status is a first-party cookie. This type tends to be less controversial because it directly relates to the site’s core functionality and the user’s selected preferences.

Third-party cookies are placed by a domain different from the one we are currently visiting. For instance, if a news site integrates an advertising service, that external service may store a cookie in our browser even though it doesn’t belong to the main site. This allows outside parties to track activity across multiple websites, often leading to heightened concerns about privacy and data collection.

Let’s compare the two cookie types:

Criteria

First-Party Cookies

Third-Party Cookies

Source

Set by the site we are currently visiting

Set by a domain different from the one we are currently visiting

Usage

Used mainly for sessions, preferences, and login status

Often used by advertisers or analytics providers to track behavior across multiple sites

Scope

Limited to the single site that created them

Can be accessed by multiple unrelated sites, enabling cross-site tracking

Privacy Concerns

Generally viewed as less intrusive

Raise significant privacy concerns due to extensive monitoring

Browser Treatment

Widely accepted by default

Increasingly blocked or restricted by modern browsers due to privacy considerations

6. Techniques and Methods for Tracking with Cookies

The straightforward method of using a single cookie to identify a user and track their visits can become more sophisticated in practice. Advertisers and analytics companies employ numerous techniques to ensure they can follow users accurately.

One popular technique involves embedding small images, known as tracking pixels. These pixels are hosted on a server controlled by the tracking company. When we load a page, our browser requests the pixel, and that request can include a cookie. This lets the tracking service note that the same browser has appeared on a new page.

In addition, scripts running in the background can set or read cookies as we navigate through pages. These scripts might correlate multiple identifiers, combine the data from cookies with other browser fingerprinting methods, and store detailed logs. Trackers can overcome some restrictions and maintain consistent user profiles by linking cookie-based identifiers with device-specific data.

Over time, this analytics and advertising ecosystem developed highly complex infrastructures. Even as newer methods like browser fingerprinting gain traction, cookies are the simplest and most widely recognized instrument for persistent identification. Their longevity and broad browser support make them a convenient solution for those seeking to observe user behavior over time.

7. Legal and Regulatory Aspects

The widespread use of cookies for tracking has not gone unnoticed by regulators. Various laws and regulations have emerged to address privacy implications. Prominent frameworks, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, require websites to obtain user consent before setting certain non-essential cookies, especially those used for tracking and advertising.

In addition, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and other regional regulations encourage transparency in how data is collected and used. Under these frameworks, organizations must inform users about cookie usage and, in some cases, provide mechanisms for users to opt out.

Compliance often involves adding cookie notices or consent screens that present clear choices. Instead of hiding what is happening, the idea is to let users simply say “yes” or “no” to the cookies that track them. For example, someone might agree to cookies that keep the site working properly but refuse those that follow their actions across different pages to show them ads. By giving users a straightforward way to decide, the regulations shift more power into their hands.

In practice, this doesn’t always work smoothly. Some websites rely on what are known as dark patterns to push users toward accepting all cookies. A dark pattern might make the “accept all” button bright and easy to click, while the “reject” option is hidden, hard to read, or buried behind extra steps. Confusing words and complex layouts can trick users into giving consent without fully understanding their choice. Regulators are watching these tactics closely, issuing fines and new guidelines to ensure websites are open and honest. As a result, cookies are no longer operating quietly in the background; they have become a central part of major discussions about online privacy and proper conduct.

8. User Controls and Mitigations

Most modern web browsers provide tools to manage cookies. We can clear cookies, block third-party cookies, or use more advanced browser settings to limit tracking. Privacy-focused browsers often have built-in protections against trackers, including blocking known third-party cookies or blocking fingerprinting techniques.

Browser extensions can also be useful. Tools such as privacy filters or content blockers identify known trackers and prevent them from setting or reading cookies. By doing so, they break the chain of identification that cookies enable.

In addition to technical tools, user awareness plays a key role. Understanding that cookies can be used for more than just remembering login details encourages users to question cookie consent banners. If a site asks whether we want to allow marketing cookies, we can decline. Some users prefer to browse in private or incognito modes to reduce the persistence of cookies. While incognito modes don’t prevent tracking entirely, they limit how long cookies persist between sessions.

9. The Future of Tracking and Cookies

The landscape of online tracking is shifting. Modern browsers are increasingly restricting third-party cookies by default. For instance, some have started phasing them out or blocking them entirely. This has led marketers and advertisers to search for other tracking methods, such as browser fingerprinting or using first-party data more cleverly.

On the regulatory side, the trend points toward stricter privacy laws and enforcement. Each year, authorities encourage or mandate practices that respect user choice. As a result, companies must adapt and find ways to deliver relevant content without relying on invasive monitoring.

An interesting development is the emergence of privacy-preserving standards that could replace traditional cookies. Some proposals suggest storing less personal data or using aggregation methods that don’t track users individually. These ideas seek to balance the interests of advertisers, publishers, and users. If they gain traction, the industry might move toward a model that provides some personalization without keeping detailed personal histories.

At the same time, user education is improving. With more resources explaining cookies and tracking, web users have a clearer idea of how their data is collected and why. This push toward greater transparency and awareness will likely influence web technology design. Instead of quietly relying on cookies for broad data collection, the future might demand open disclosure and meaningful choices.

10. Conclusion

In this article, we discussed cookies as a concept that has evolved from a simple tool for preserving user sessions into powerful mechanisms that enable tracking and profiling across many areas of the web.

As regulations tighten and users become more informed, the future of cookies depends on balancing convenience with a growing demand for privacy and control.